By the end of this module, you’ll gain experience with cloud networking, virtual private clouds, and IP addressing.

Module videos:

- Cloud Networking Basics [11:30]

- VPC Networks and Firewalls [20:01] (1/2)

- VPC Networks and Firewalls [12:55] (2/2)

- (Google) Migrating to GCP? First Things First: VPCs [7:25]

Cloud Networking

Time to discuss networking! Sure would be a shame if all those nifty services you’re working on couldn’t talk to the rest of the world, right? Well, here we’re going to cover how to get them all talking.

Take what you know of standard networking and scale it up significantly, and you have cloud networking. Sandboxed networks? Yep. Subnets? Yep. Network partitioning and load balancing? Sure!

Plus a lot more, time to get into it.

Here are a few videos to get you up and running, covering the basics of cloud networking, what VPC networks are and how they differ, and the great firewall:

- Module video: Cloud Networking Basics [11:30]

- Module video: VPC Networks and Firewalls [20:01] (1/2)

- Module video: VPC Networks and Firewalls [12:55] (2/2)

- Module video: (Google) Migrating to GCP? First Things First: VPCs [7:25]

Networking Background

A quick refresher on terminologies:

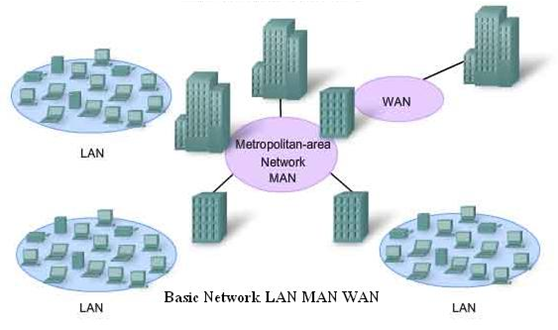

- Devices in a single location are connected via local-area network (LAN). Only devices participating in this network can talk to each other (VPN connections are considered to be ‘local,’ though can be treated differently).

- Wide-area networks (WAN) connect multiple LANs together, enabling a wider range of communication.

We’ll skip the less-commonly-used metropolitan-area network. Just consider that, in present times, most devices are connected to the Internet, which is effectively just a WAN of massive scale.

LAN vs. MAN vs. WAN (c/o Viva Differences)

With networking at scale comes the benefit of being able to work with your infrastructure and devices remotely (i.e., if a fire (either literally or figuratively) starts in the middle of the night, all you need to do is login and remotely fix the problem).

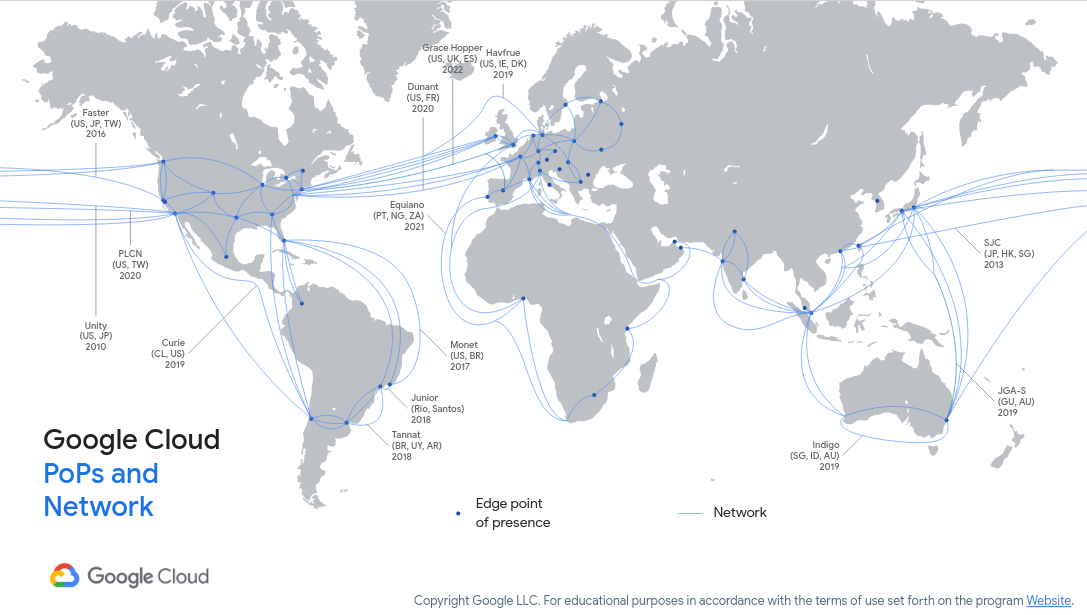

Figure 1 (c/o Google) shows an image of their private network and access points as of 2020. AWS and Azure provide similar capabilities; if you want to have a fast response from your cloud provider then you will need nearby access!

Figure 1: Google Cloud Network

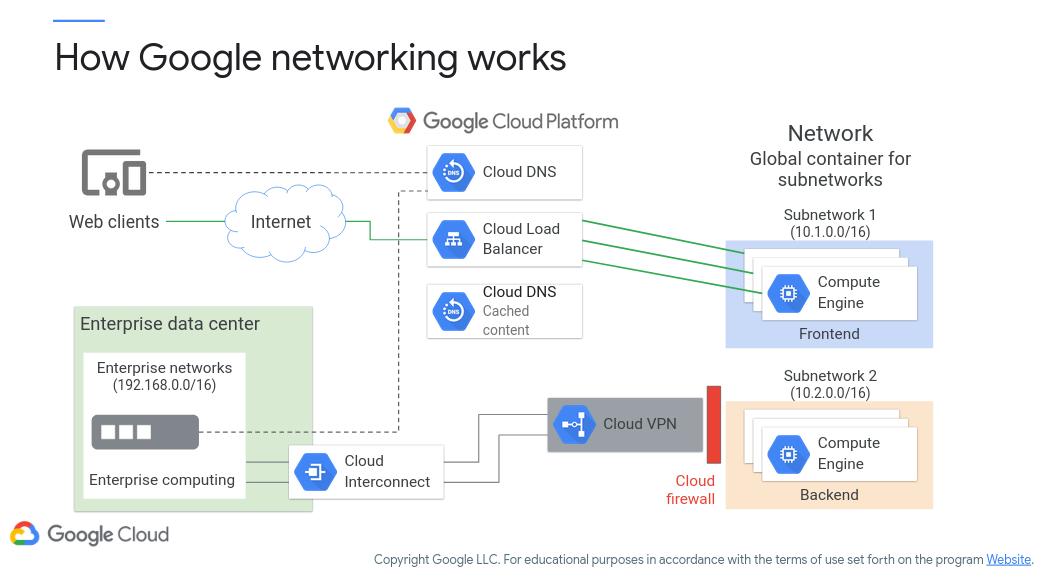

Let’s say that you want to connect your infrastructure to Google Cloud (or similar). To do so you will need to provide some sort of connectivity between your servers and your cloud provider’s. Figure 2 (c/o Google) shows their strategy for doing so. Here, you’ll notice how a service-oriented cloud architecture can hook into yours. For instance, your data center can connect to Google Cloud Interconnect (a service for extending your network to Google’s) and then to Cloud VPN (a service for connecting to a virtual private cloud network). Alternatively, your servers and/or your clients can connect directly to the various cloud services as well. These can be supported by name resolution services (i.e., Cloud DNS) and load balancing (i.e., Cloud Load Balancer) for distributing traffic amongst servers.

Figure 2: Google Cloud Networking

Virtual Private Cloud (VPC)

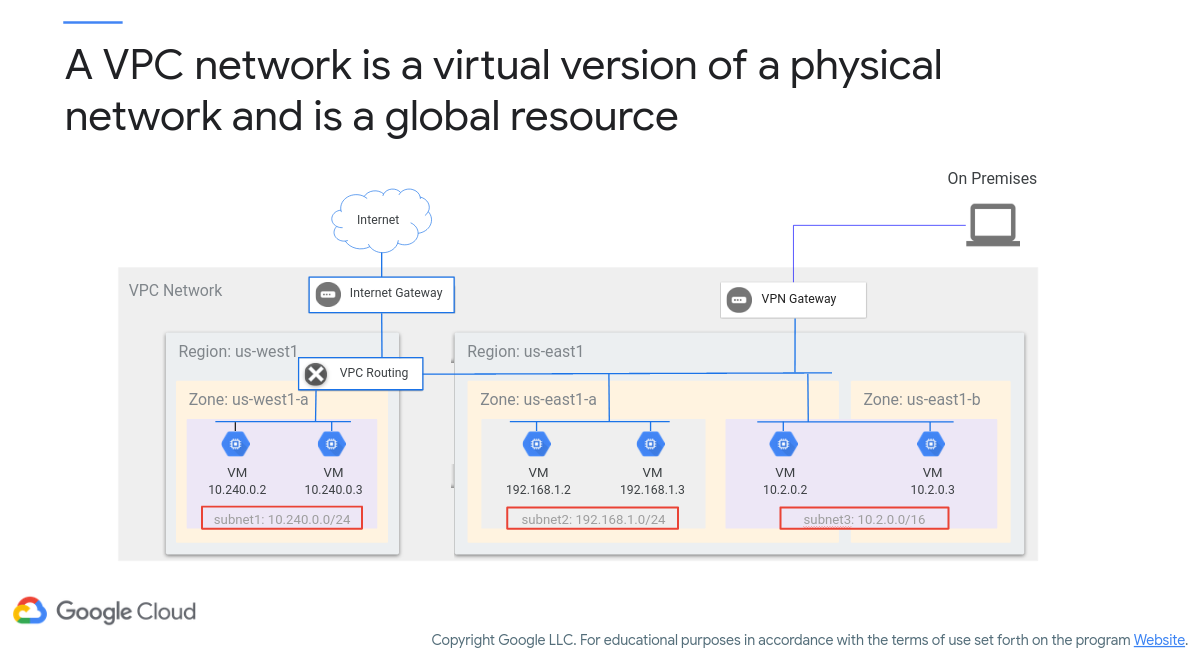

A VPC network is essentially a small sandboxed network for your projects to live in. They are built on top of the Google private networking environment. Here, you can apply many of your “usual” techniques for securing a network (firewalls, access control, etc.). VPCs are software-defined network (SDN) constructs that can be used for deploying services such as compute instances, containers, etc. There are no ‘real’ IP address ranges (they must be defined as subnets and then internal ranges tend to be 10.* and external are at the whim of Google). VPCs are global in nature as well, meaning you can access your VPC from any location that has Internet access. You can also create sub-networks (subnets) as well in particular regions or zones for partitioning your VPC network.

Figure 3 (c/o Google) shows an overview of a VPC network, comprising subnets that are region/zone specific. Here, you can see how an on-prem (or remote) client can connect remotely to a VPC network to access Compute VM instances in various regions.

Figure 3: Google Cloud VPC Network

The figure above shows how subnets are regional resources. If you want a usable set of IP address ranges, then a subnet must be created (otherwise, you get the ‘default’ IP address range). Interestingly, virtual machines in different zones, but in the same region, can share the same subnet!

Back to Figure 3, you see subnet defined as 10.240.0.0/24 in us-west1. There are two virtual machine instances in zone us-west1-a. Their IP address assignments come from the range specified for subnet1.

subnet2 is defined as 192.168.1.0/24 in us-east1 (region). There are two virtual machine instances in zone us-east1-a, where their IP addresses are defined from subnet2.

Now, subnet3 is set to be 10.2.0.0/16, but also within the us-east1 region. There is one virtual machine in zone us-east1-a and another in zone us-east1-b, where both virtual machines get their IPs from the range available to subnet3. They may each have their own network interface (as a result of being a regional resource), however still can talk to each other as they’re on the same subnet.

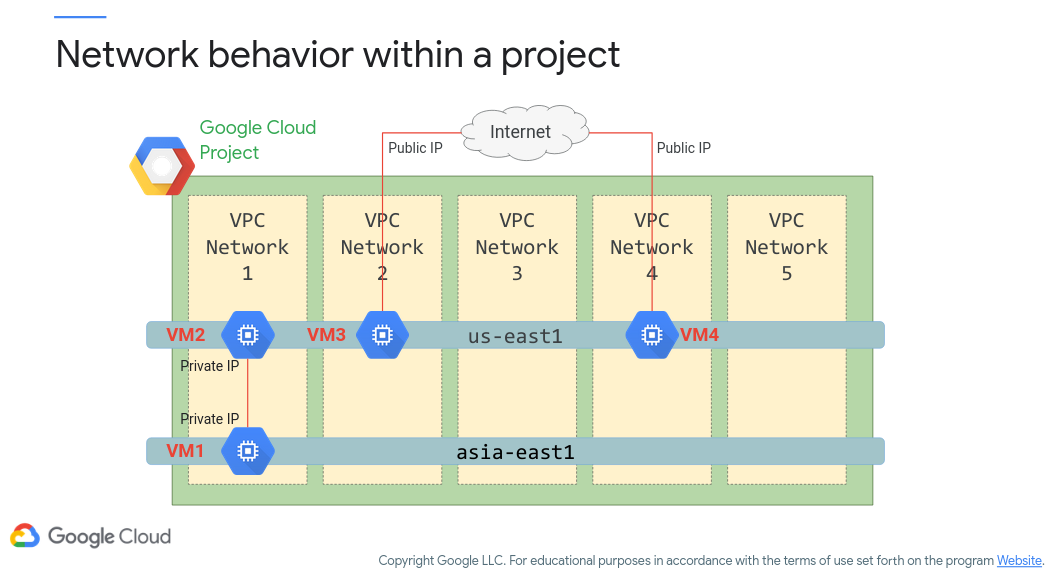

Figure 4 (c/o Google) shows how resources in different regions yet the same VPC can communicate. For instance, VM1 and VM2 can communicate locally as they both reside within VPC Network 1. They are separated geographically (us-east1 and asia-east1), however by merit of being in the same VPC network they can directly talk. However, for resources in different VPC networks an Internet connection must be made. For example, if VM3 and VM4 want to talk they will need to use their public IP addresses rather than their private IP addresses (even though they’re in the same region).

Figure 4: Network Behavior

Subnet Creation Modes

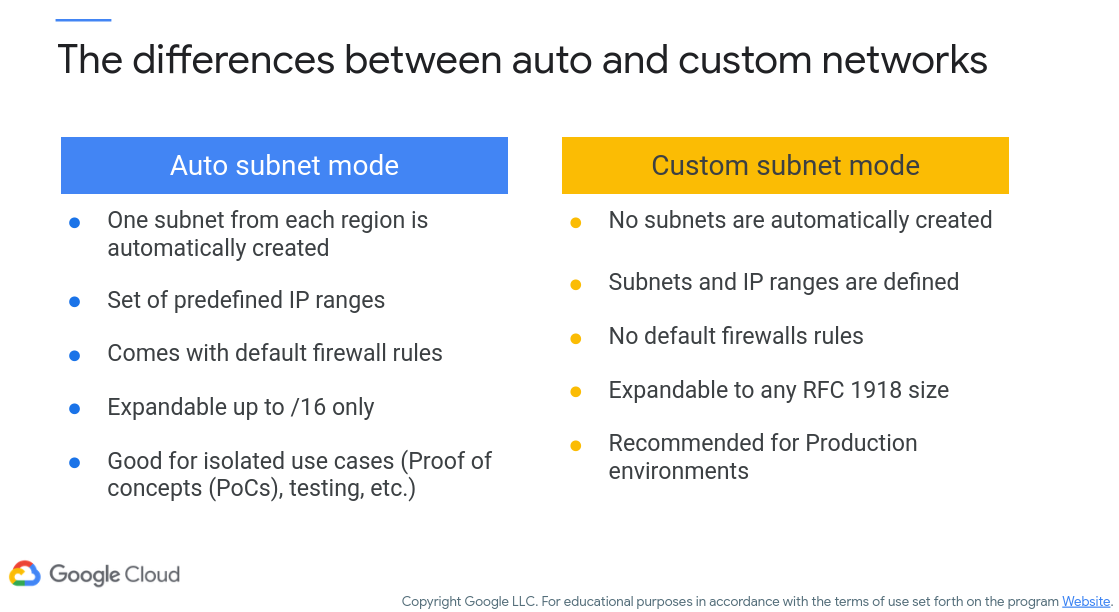

Subnets can be created automatically or via custom rules. While we’re not going to spend too much time on this topic, note that automated creation tends to be good for proof-of-concept builds, whereas the finer-grained control (and less hand-holding) of the custom build is more suitable for production (Figure 5, c/o Google).

Figure 5: Auto vs. Custom Subnets

IP Address Ranges

Let’s take another trip down networking basics and talk about IP address ranges (as you should be specifying them as part of your subnets). This won’t be comprehensive as we’ll leave that to undergrad networking classes, but more of a refresher.

This is important for VPC networks as you will need to specify the IP address ranges.

There are four octets of bits that make up an IP address. For instance, 10.0.0.1 represents four octets – this translates to 0000 1010. 0000 0000. 0000 0000. 0000 0001 in binary. Depending on your network needs (do you have few clients and many networks, many clients and less networks) you can opt to freeze a portion of the IP address range. Note that this decision is normally left to your internet service provider or network administrator. You may notice that, on your home network, all your devices tend to be on the 192.168.1.X range (these are private addresses used internal to your network). Unless otherwise configured, 192.168.1 is set by your router and all the clients that connect to your router will be identified by that final octet (e.g., your laptop is 192.168.1.2, your phone 192.168.1.4, etc.). Remember that an IP address needs to be unique, otherwise your device will not be able to properly communicate on a network!

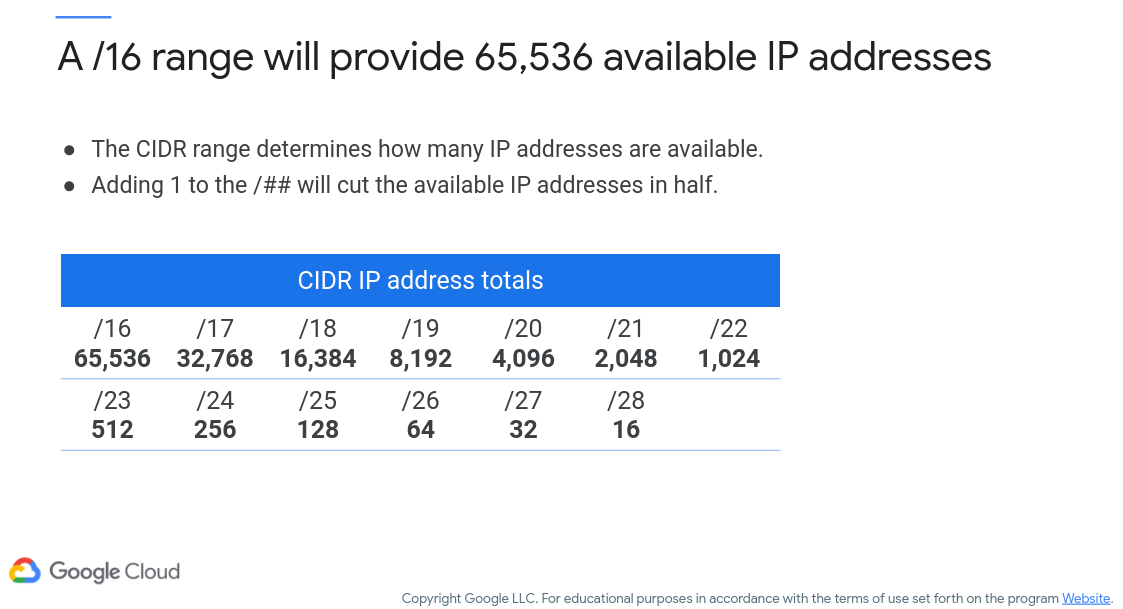

The important aspect here is the little slash designator you see at the end that we introduced earlier. For instance, 10.0.0.0/16 tells the network that the last 16 bits are to be varying, and the first 16 bits are frozen. An IP address in this range would always start with 10.0 and the remaining bits would be dynamically assigned to devices that connect to the network (assuming we’re using DHCP that is to manage IP addressing). By setting the number of devices in such a way, you are telling the network how many clients you wish to support. Figure 6 (c/o Google) shows how many clients can be assigned IP addresses at the same time with various specified ranges (CIDR – Classless Interdomain Routing).

Figure 6: IP Address Ranges

Internal vs. External IP Addresses

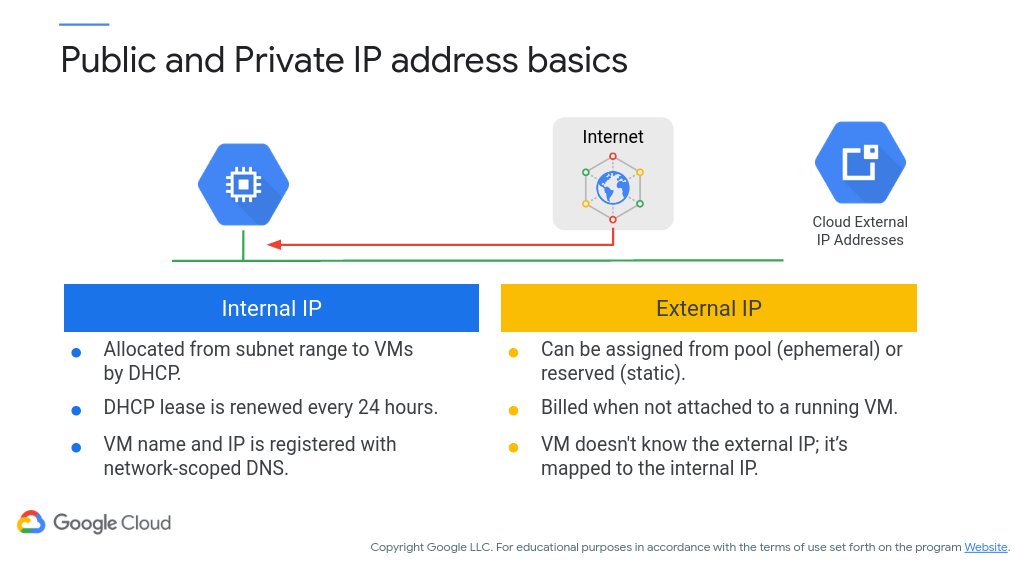

One consideration for cloud-based systems are how your devices/services are addressed. Generally, you will have internal IP addresses and external IP addresses available, where internal are accessible only within the VPC network and external are public-facing (another reason to lock down your services with IAM!). Figure 7 (c/o Google) gives you an idea of the differences between the two.

Figure 7: Internal vs. External IP addresses

One important thing to note is the lease time on IP addresses. Internally, you can generally reference objects via their host name that is then translated via an internal DNS server (so, IP addresses changing every 24 hours is not a large concern unless if you’re manually specifying the IP address in other services). However, external IP addresses can change as well (you can set it to be static, however this comes at a cost).

Let’s take an example. You setup a web server on a Compute Engine instance and run a web application from that virtual machine. You take no action for IP addressing and let Google handle it. By default, all addresses are ephemeral and are essentially DHCP-assigned and rotated. You then hook your web application up to a domain registrar and setup a domain name. You reboot your server for updates at some point and, oops, the IP address has changed! Now, nobody can access your web application until you update your domain registrar. You can reserve an IP address, however it must be attached to a virtual machine otherwise you’re billed for it (see above figure).

Routes and Firewalls

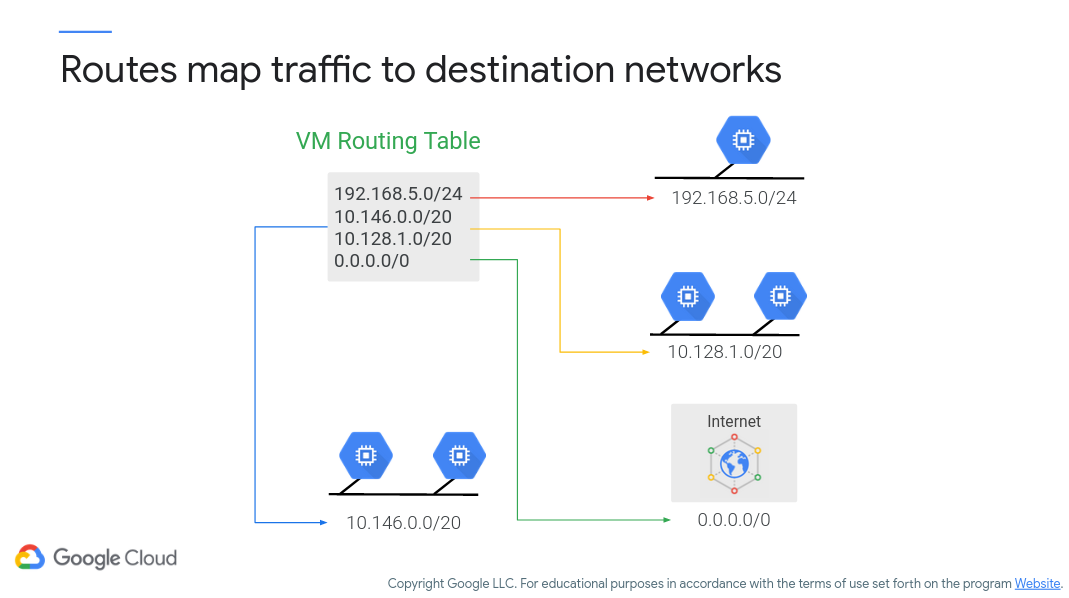

Time to keep out the unruly public from our private resources! Let’s talk about firewalls and routes now. First of all, routes. A network will:

- Allow instances/services within a network to talk to each other via defined routes

- Have a default route that directs packets into/out of said network

- Have a firewall that allows or drops packets as directed

Basically, routes are defined to tell network packets where to go (both coming in, going out, and in between). As the admin of this virtual cloud, you have the ability to configure these behaviors along with additional custom routes as required. You also can configure the firewall to enable/prevent access to your VPC network on various IP address ranges and ports. Figure 8 (c/o Google) shows how routes direct traffic within VPC.

Figure 8: VPC Routing

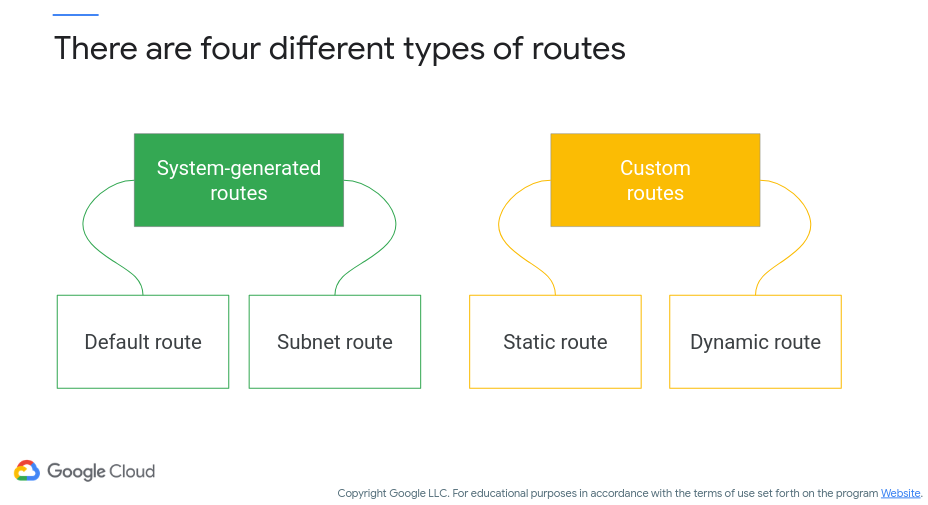

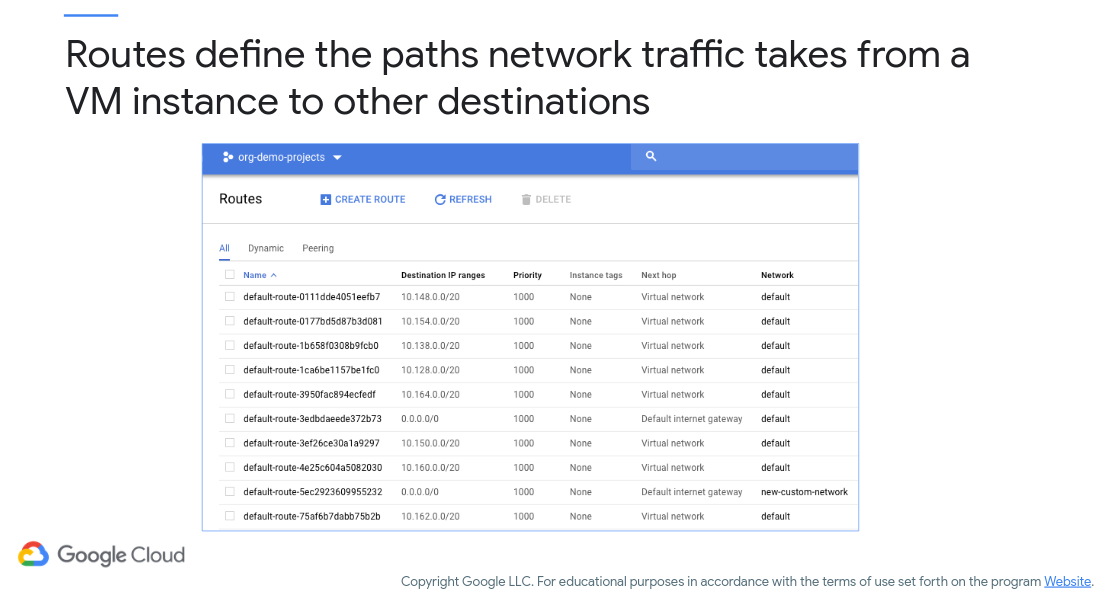

Figure 9 (c/o Google) shows the different types of VPC routes that can be specified, where these include system-generated and custom (i.e., specified by you). Figure 10 (c/o Google, again) shows a sample routing table, including system-defined and custom-defined routes.

Figure 9: VPC Route Types

Figure 10: VPC Route Table

Routes are one thing, but firewalls will help keep your network protected (and will also probably make you pull your hair out when you can’t figure out why your external applications can’t access your internal (VPC) services/instances).

Here are a few points on Google Cloud VPC firewalls:

- VPC network functions as a distributed firewall

- Firewall rules are applied to the network as a whole

- Connections are allowed or denied at the instance level

- Firewall rules are stateful

- Implied deny all ingress and allow all egress

Basically, the point to keep in mind is that there is an implied Deny All rules for ingress (i.e., incoming connections) and Allow All for egress (i.e., outgoing connections). I’m simplifying here, but there is a great deal of information available on Google Cloud Firewalls to peruse.

However, the best way to get comfortable with VPC networking is with hands-on activities. Here is a lab I’d like you to run through (see assignments in Blackboard for deliverables). It will give you experience with VPC connectivity and access control, respectively:

Load Balancing

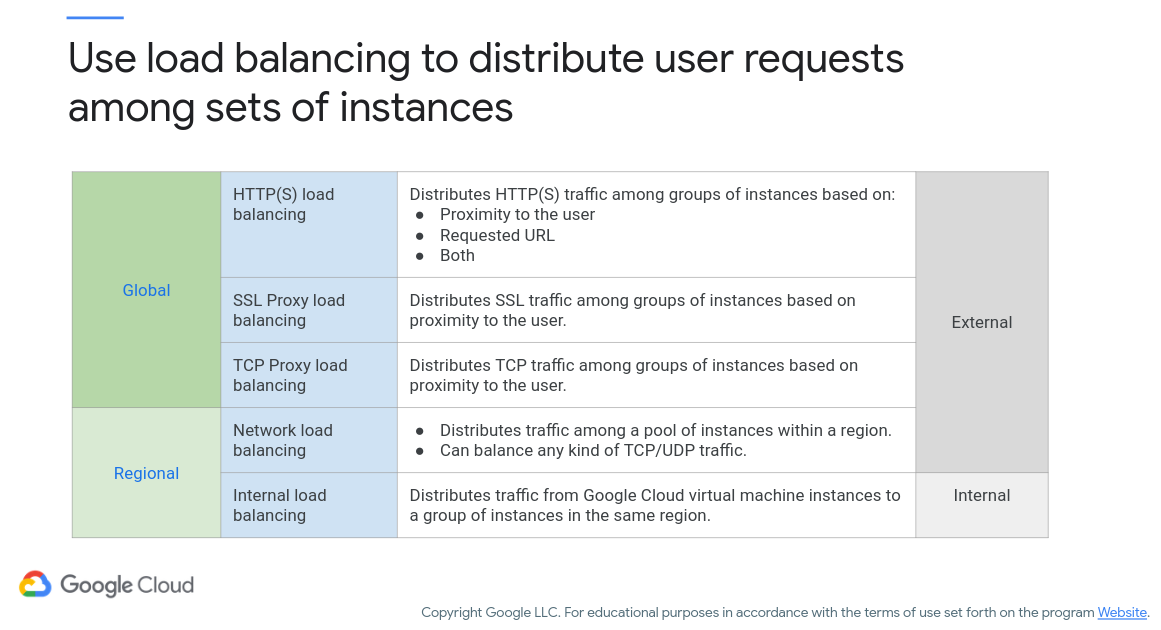

Since you’re building your apps in the cloud, you’re probably going to expect to have a lot of users. To support your growing userbase you can take advantage of load balancing, or redirecting your clients to servers that are not overloaded. Figure 11 (c/o Google) shows some of the options you have here.

Figure 11: Load Balancing

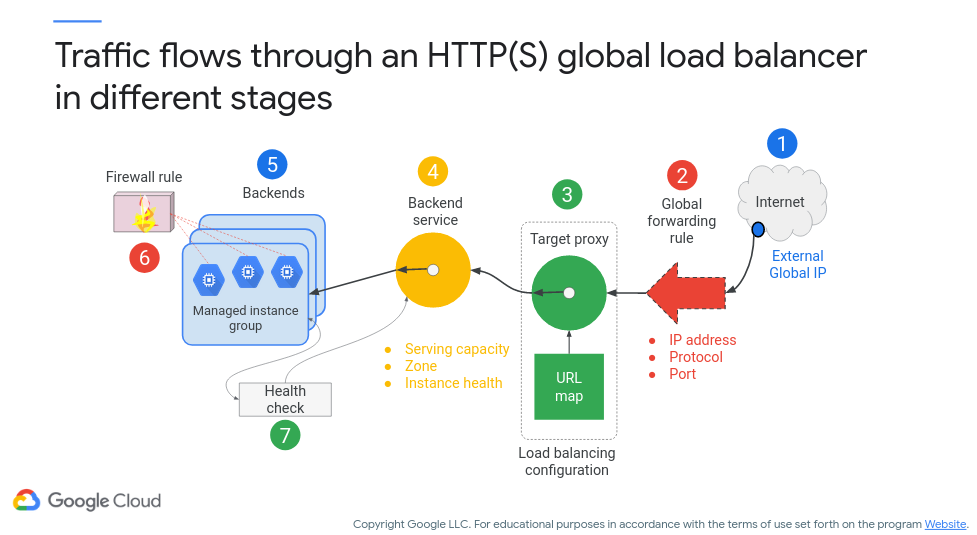

Essentially, you can set how you want your network load to be distributed (and yes, this can be based on the routes that we talked about earlier). Let’s take a look at an HTTP load balancer (i.e., distributing traffic amongst web servers) in Figure 12 (c/o Google) - note that the numbers in the figure demonstrate the order in which traffic is routed:

Figure 12: HTTP Load Balancer

In step one, traffic gets routed to an external regional IP address that’s associated with a global load balancer. External global IP addresses cannot be assigned to any regional or zonal resource. In step two, the global forwarding rule will forward traffic to a target proxy. In step three, the target proxy can either forward traffic backend service or use URL maps that can send traffic to specific managed instance groups based on the URL. For step four, the backend service will track the serving capacity and instance health of each backend and always send traffic to the backend that is closest to the user that has capacity. For steps five through seven, the backends can either be a managed or unmanaged group of instances. Firewall rules and health checks will help determine if traffic will reach the instances.

To help you understand load balancing, we’ll run through another QwikLab. It will help you learn how to setup an HTTP load balancer (similar to the above figure) and load balance based on internal workloads, respectively (again, see Blackboard for deliverable expectations).

Additional Resources

Where noted, the original content was provided by Google LLC and modified for the purpose of the course, without input or endorsement from Google LLC.