By the end of this module, you’ll gain experience with cloud security and provider vs. consumer responsibilities with respect to security.

Module videos:

Cloud Security

Security is a consideration from both the perspective of the cloud provider and from you, the developer. While we can rely on our provider to enable perimeter security (e.g., firewalls/walled gardens) as well as provide internal security (e.g., automatic encryption), it will eventually fall on you to implement the necessary security protocols relevant to your task. Specifically, one of the biggest causes of security issues is from mis-configured services/applications that expose a weakness, from poor password management to over-authorizing accounts. We’ll go into all of that in this post, but first lets start with a short overview of the encryption/decryption possibilities available to us, as well as some of the roles we can specify, along with to which entities we can apply those roles:

- Module video: Cloud Security Overview [15:36]

- Module video: Cloud Encryption Overview + IAM + Roles [14:42]

Google Cloud Security Model

For reference, here are links to Amazon’s and Microsoft’s cloud security models:

If you were to read through the articles (and I suggest you do … nice to see what the other providers do as well!), you might notice some similarities. Most notably the shared responsibility model! What this means is that the cloud provider …

IS NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR ALL YOUR SECURITY CONCERNS!!!

Keep this in mind as you have responsibilities as well. One of the biggest points of weakness in any cloud-based application is in not understanding how security works. By this point you should realize that security is a concern; I am certain you all have heard of data leaks, hacks, etc., in large companies or cloud hosts. Private data being leaked, pictures stolen, backdoors discovered, etc. All of these problems tend to stem from weak security rather than coordinated efforts (though such efforts do exist, let’s not trivialize that).

Now, the provider does have some responsibility in this matter and does provide you the capabilities to secure your applications. However, if you do something silly like set a trivial password for your virtual machines then all that sophisticated security is useless.

Personal example! I had a group of students learning on temporary Windows virtual machines and had them set a password of

Temp12345for a login. Oddly enough, some of the machines were hacked and turned into a Bitcoin-mining botnet. Google quickly realized what was happening and shut down the machines and sent me and the students a nasty-gram, however it was a sobering learning experience. How were the machines discovered, you might ask? Well, there tend to be a lot of bots on the internet constantly scanning for weakpoints, poor passwords, etc. They most likely were targeting Google-specific IP address ranges and were testing for points of failure. Well, they found one!

The point of this little diversion is that your cloud provider will do its best to provide a good perimeter defense against attacks. However, you are just as important in this chain of security as your users and your provider are. The provider can sandbox your services/tools such that others aren’t impacted, but those services/tools/virtual machines/etc. that you make publicly available sure can be impacted. Essentially, you yourself must configure security appropriately. You must understand how the tools work, understand the current best practices, continually keep learning and understanding how security threats evolve over time, and educate your users to not needlessly expose themselves to attack.

(The reason I added the bold font in that last sentence was that security attacks and threats are always evolving – so too must you as the architect of your cloud applications!)

Keep in mind that lost data not only introduces technical concerns, but the trust you may have built with your users is completely lost. Would you trust a company with your business if they can’t be bothered to practice basic security principles?

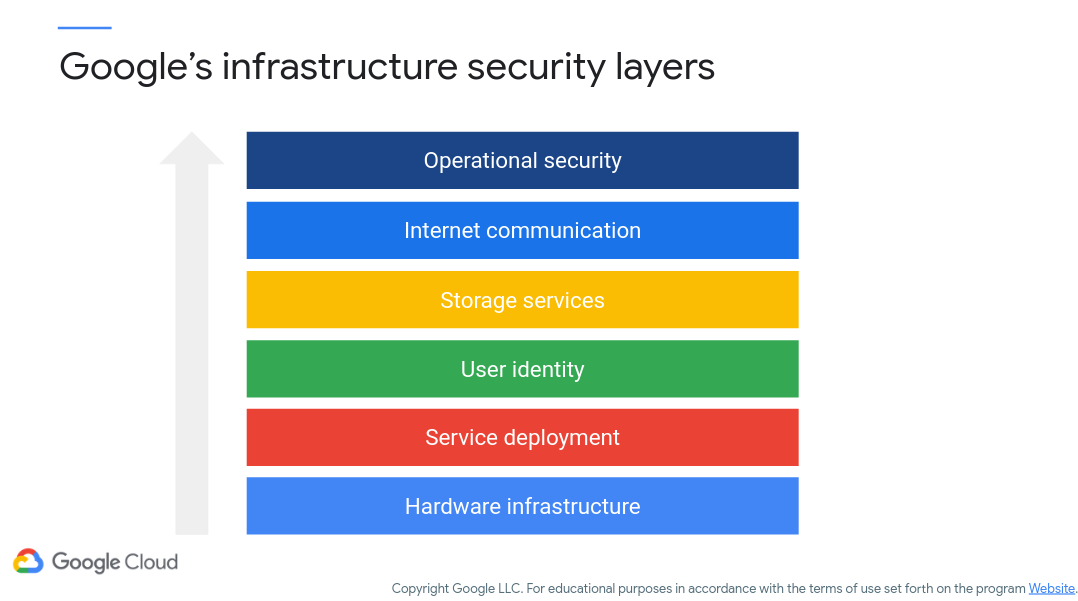

Ok, soapboxing complete. Let’s look at what Google does from a security perspective. Figure 1 (c/o Google) presents a view of their infrastructure security layers:

Figure 1: Google Infrastructure Security Layers

This figure demonstrates that security must be built into every single layer of the system as a whole, from hardware to operational security. Essentially, security must be distributed throughout all aspects of a project, thereby reducing single points of failure!

From the cloud provider’s perspective, consider the sheer number of users (i.e., you) that want to leverage what is possible to build their own applications. They will sandbox each user to the best of their ability, meaning that you will not have access (unless otherwise allowed, either via authorization, delegation, or access via encrypted remote procedure calls) to anybody else’s account!

Another consideration is that many cloud providers will have some sort of ‘bug bounty’ program in place, where if you discover a problem or bug you may be rewarded for it. In this regard, both providers and the community (either from industry or research) can advance the state of the art when it comes to security.

Shared Security Model

It is now time to really dig into shared security! But what does it mean to share security? If you create a ‘normal’ application, you are in charge of security of all aspects, from physical access to terminals to remote access to data. In a shared security model, some responsibility falls on the provider and some falls on the developer (or architect). Figure 2 (c/o Google) next illustrates the shared security responsibility between Google and the user (note: this model may not hold for all providers – check with whichever host you select!).

Figure 2: Google Cloud Shared Security Model

Note that Google’s responsibility for security increases with the amount of their provided service. Generally, your cloud provider will secure the physical infrastructure necessary (e.g., the servers, disks, etc.). However, the provider won’t usually be responsible for securing your users’ accounts, ensuring that you protect valuable resources, require you to use authorization/authentication on your public-facing services, etc. Note that you can set a Cloud Function to be triggered via a public HTML call, however this means that anybody can trigger it (and as many times as they want). Pay attention to security please!

What we’ve been mainly discussing so far is how you configure your applications and how you enable your customers to use your world-changing cloud application. However, we have yet to really discuss data. One point to keep well in mind is that data access is pretty much always going to be your responsibility to manage. You the cloud customer can distribute access as necessary, however the cloud provider isn’t going to intuitively know who needs what access; that’s your job! The provider does provide the tools necessary to manage access rights (e.g., Cloud Identity, Access Management, etc.), however it is up to you to configure that.

Next, let’s go over encryption possibilities.

Encryption

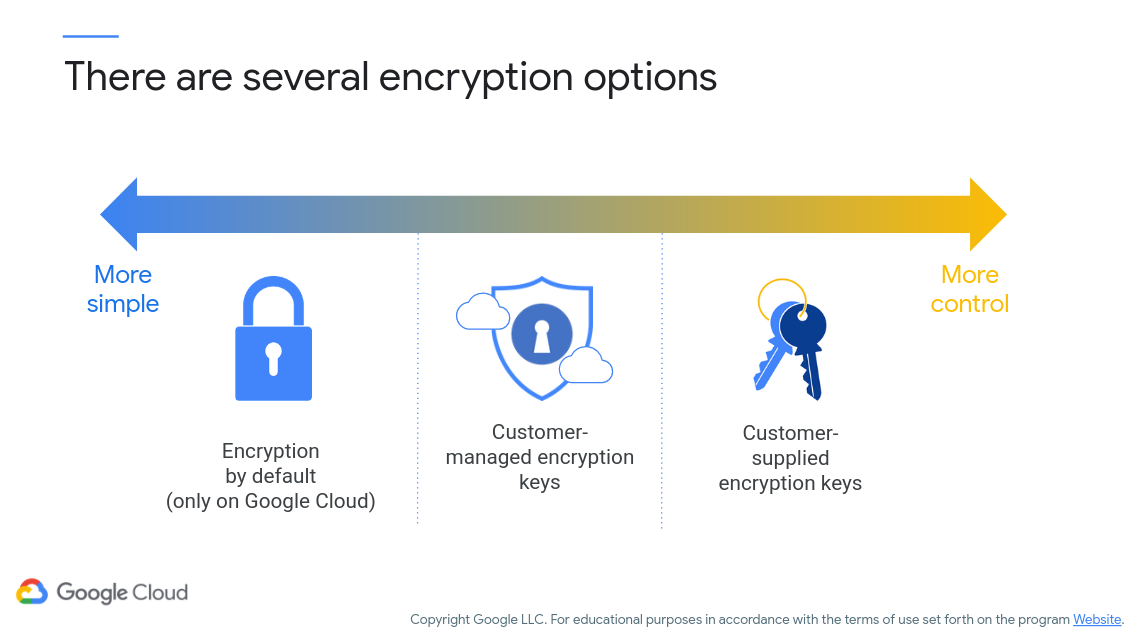

This is not a class on encryption, so therefore I am going to make the assumption that you understand (or can understand) how encryption and decryption of information works. If not, here’s a nice overview. Figure 3 (c/o Google) demonstrates the encryption options available to you as a developer:

Figure 3: Google Cloud Encryption Options

Looking at this figure you realize you have a range of options available to you. You might select a simpler option that uses default encryption procedures, however the cost is that you the developer have less control over encryption procedures. Essentially, the question here is if you want to manage encryption fully by yourself (customer-supplied encryption keys) or do you want your provider to handle some of the burden.

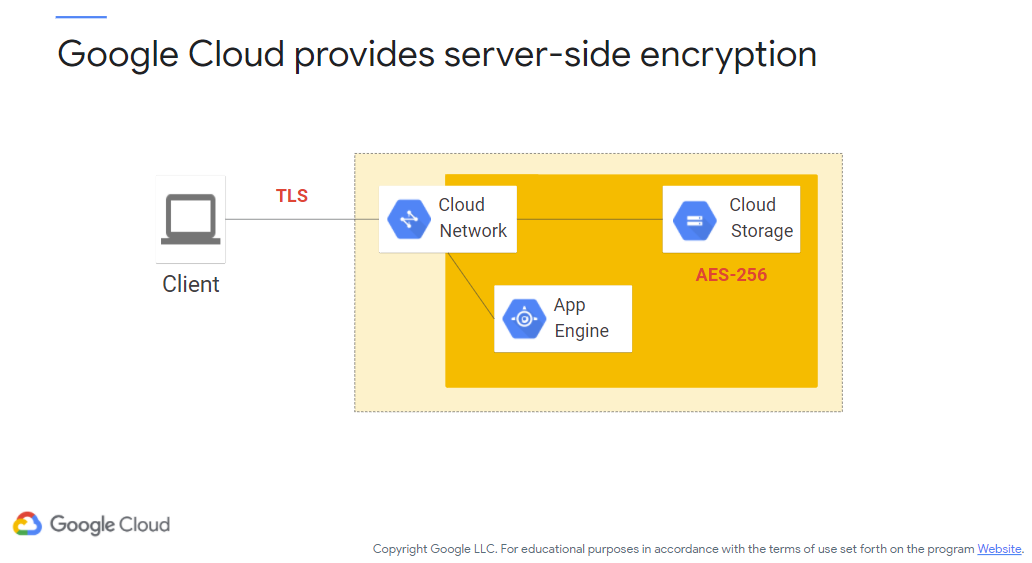

By default, Google will encrypt data in transit (i.e., being sent/received to/from the servers) using TLS encryption. Data at rest (i.e., lounging about on the servers) is encrypted via AES-256. Both happen automatically. Figure 4 (c/o Google) provides an illustration of this procedure:

Figure 4: Google Cloud Server-Side Encryption

Now to the developer-selectable options. You can choose to either use customer-managed encryption keys (CMEK) or customer-supplied encryption keys (CSEK). CMEK uses Google Cloud’s key management service (Cloud KMS) to automate and simplify key generation and management. Cloud KMS supports encryption, decryption, signing, and data verification from a cloud-based API, among other services. CSEK, on the other hand, enables you to generate and manage encryption keys by yourself. In this regard, you provide the keys, send them to Google for use with your applications/services, and rotate as necessary. The question here is if you want to manage keys yourself or have your provider manage them, and can really only be answered based on your own internal security procedures and feelings on who should have access to the keys themselves (i.e., should your own team, should your cloud provider?).

The following video walks you through an encryption/decryption demo using the Cloud KMS management system, including setting up keyrings, encrypting files, decrypting files, and a late-night breakdown!

Module video: Cloud KMS Codelabs Demo [8:20]

Cloud Identity and Access Management (IAM)

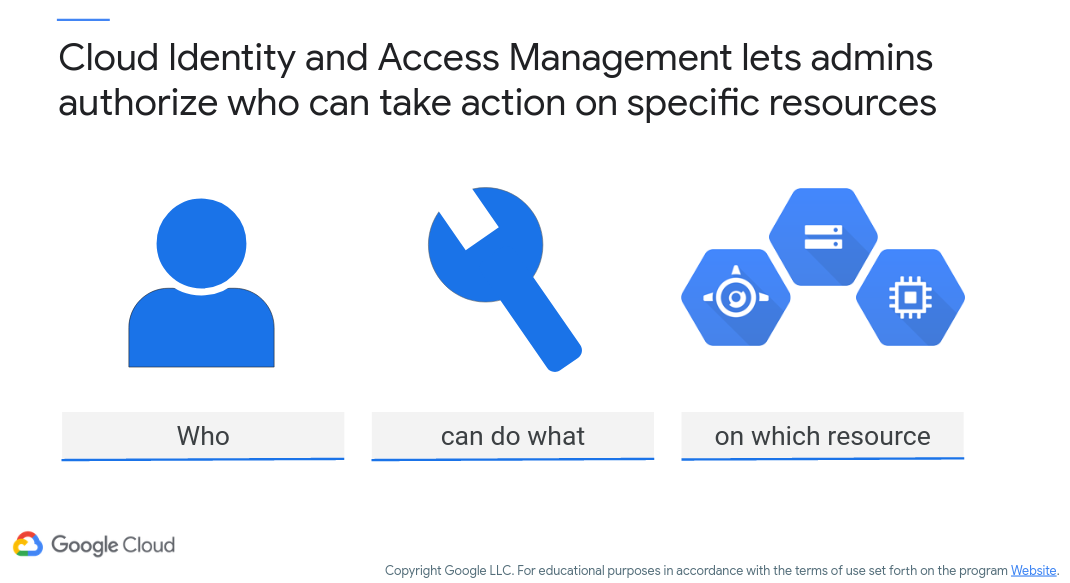

Another facet of security is authentication (you are who you say you are) and authorization (you have the rights to do

Figure 5: Google Cloud IAM

Warning, Google Cloud screenshots ahead!

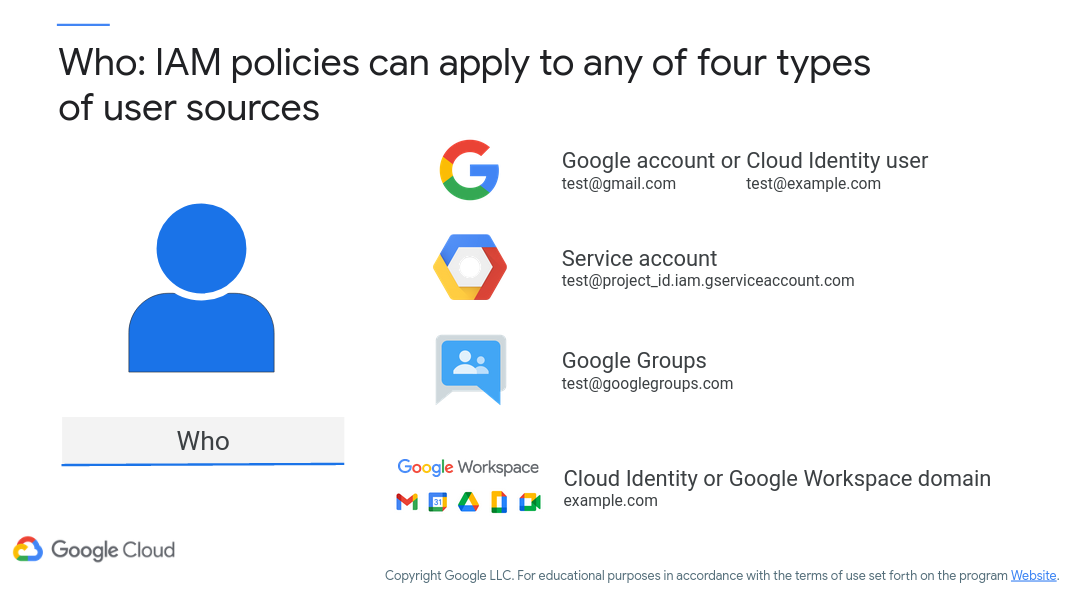

Figure 6 shows what the who in this activity means. Defining what a “who” is will differ based on your cloud provider. For Google Cloud, we’ll be using a Google account (@gmail.com), a Cloud Identity user (basically, a GSuite account with your own domain), a service account, a Google Group, or some other Workspace domain. Figure 6 (c/o Google) highlights these possibilities:

Figure 6: Google Cloud “Who”

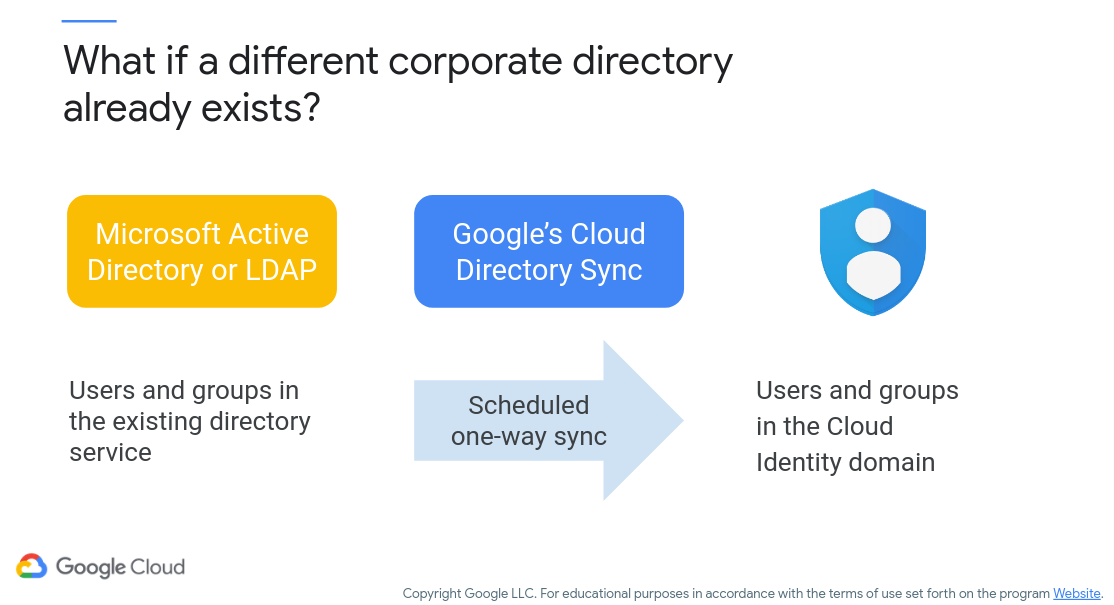

We’ll do a demo of cloud security with Google soon enough, but what if this isn’t feasible for your environment. Perhaps you’re rolling your own LDAP/Active Directory environment and you’d rather migrate that in. This is also possible to do as well! Figure 7 (c/o Google) the process flow for routing your own centralized user management service into Google Cloud by way of Cloud Directory Sync:

Figure 7: Cloud Directory Sync

This synchronization approach is only one-way however; Cloud Directory Sync can’t make updates to your local environment. However, you can schedule a synchronization process regularly (e.g., once per day). Read more about Cloud Directory Sync here.

But what if we don’t want to use Google Cloud? the student asks nervously?

Azure and AWS provide similar cloud identity management possibilities. While we won’t go into detail on them, here are links to the AWS approach and Azure approach. Note that, if you happen to be a “Windows shop” already, you can take advantage of a nice handshake between Windows Server and Active Directory for authentication.

Regardless, what we are getting towards with all this authentication/authorization business is Identity as a Service (IDaaS). You are effectively off-loading security to the cloud service provider, allowing their services to manage access rights. Neat!

Google Cloud IAM

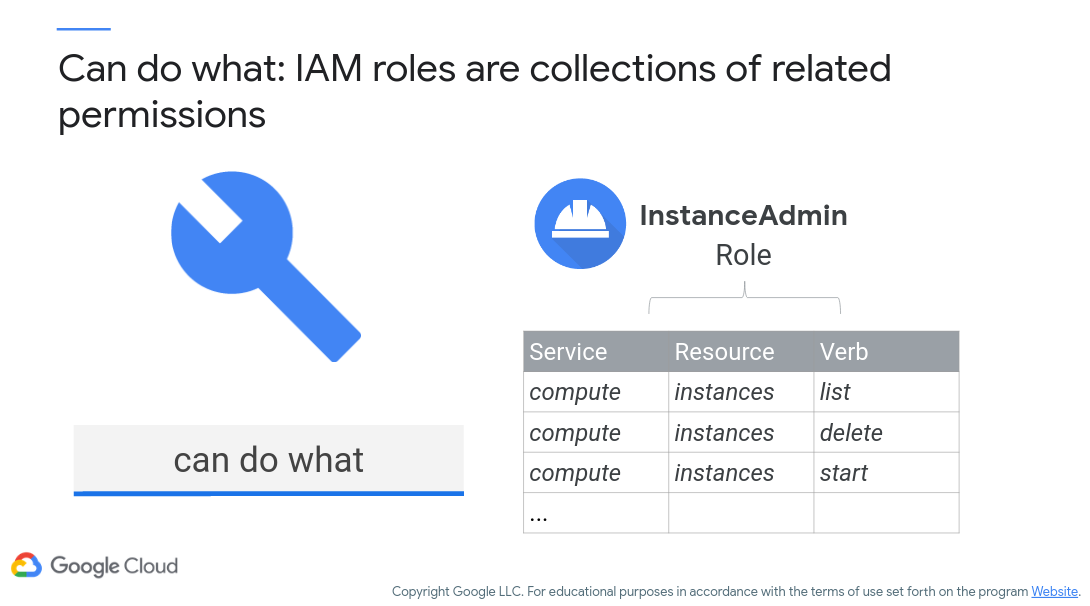

Now let’s take a look at Google Cloud IAM. Figure 8 (c/o Google) demonstrates how IAM roles and permissions are linked together. Here, permissions are very fine-grained, enabling you the cloud application developer to give very specific permissions as necessary.

Figure 8: Google Cloud IAM Example

For example, virtual machine management requires the permissions to create, delete, start, stop, and change an instance. While there are built-in roles that support these permissions (saving you time), you also can assign very specific permissions as necessary.

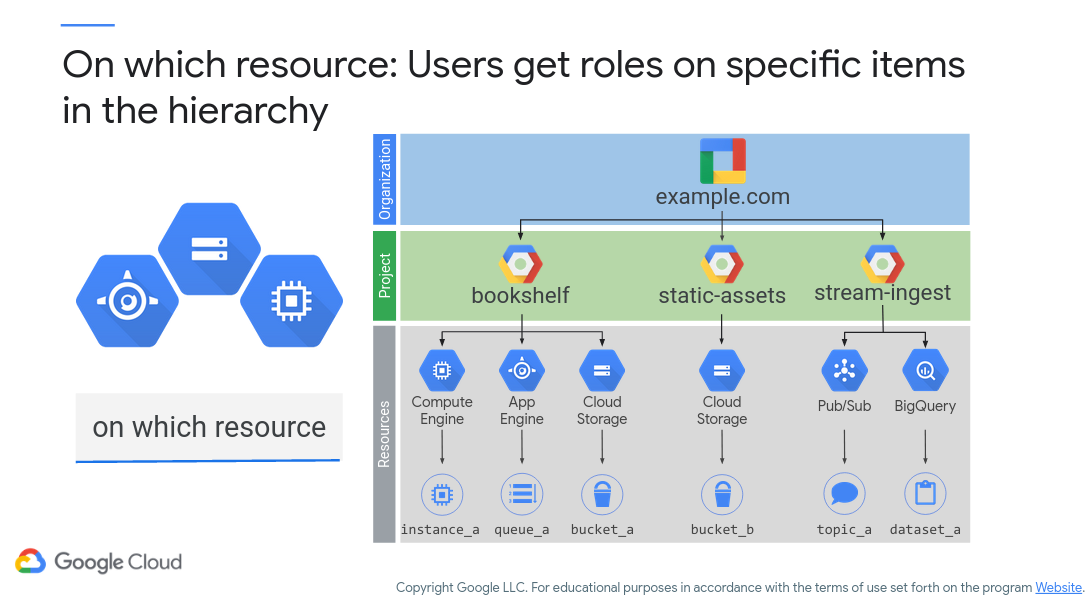

Figure 9 (c/o Google) next shows the resource-specific aspects that are a part of IAM. Here, we are demonstrating that permissions granted to a specific resource hierarchy also applies to elements below it!

Figure 9: Google Cloud IAM Hierarchy Example

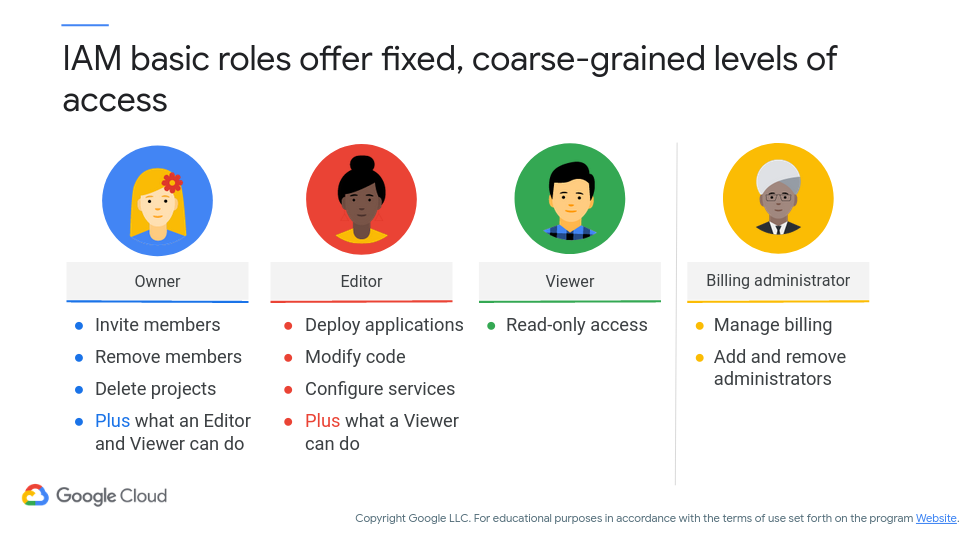

There are three types of roles in Google Cloud: basic, predefined, and custom.

Google Cloud IAM - Basic Role

Figure 10 (c/o Google) shows the different types of basic roles, plus what they are able to do within Google Cloud (by default):

Figure 10: Google Cloud - Basic Roles

The Viewer role can examine resources, but cannot change their state. The Editor role can do everything a Viewer can do plus modify state. The Owner role can do everything an editor can do, plus manage roles and permissions. The Owner role on a project also gives you control over billing and cost management. Often organizations want someone to be able to control the billing for a project without the right to change the resources in the project. You can grant someone the Billing Administrator role which grants access to billing information, but does not grant access to resources inside the project.

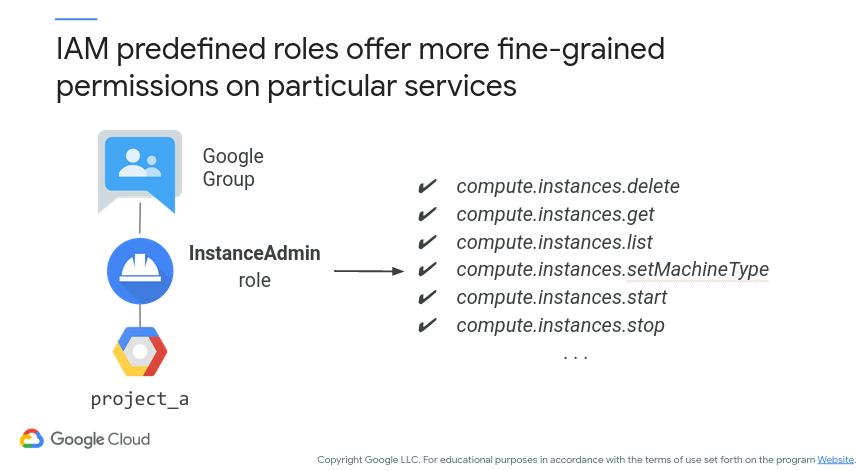

Google Cloud IAM - Predefined Role

The predefined roles apply to a specific Google Cloud service within a project. Depending on the service, you will have the choice of various roles (similar to Basic roles). However, again these are specific to a service and not Google Cloud in general! Figure 11 (c/o Google) shows how predefined roles can be tweaked as necessary. For this example, all users assigned to the Google Group shown will have the access rights specified.

Figure 11: Google Cloud - Predefined Role

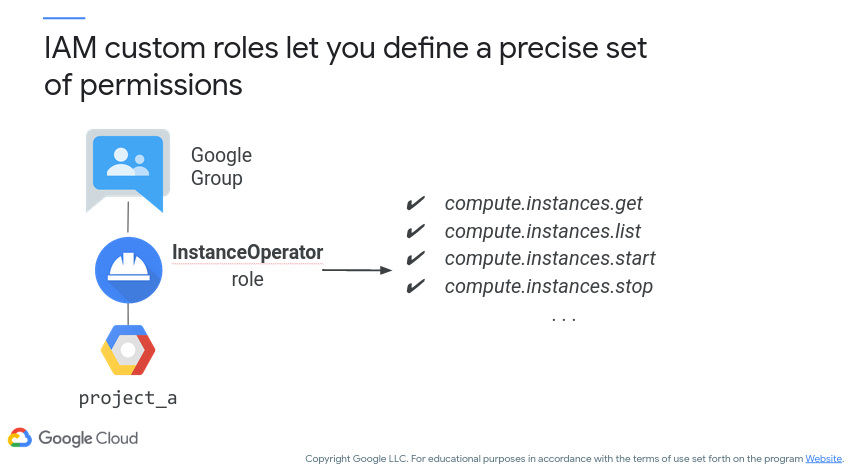

Google Cloud IAM - Custom Role

The custom role offers more granularity than the prior two. Effectively, it is up to you to design the permissions necessary for this role. If you decide to go this route, ensure that the role you are specifying only has access to the resources it needs – don’t go overboard and unintentionally introduce a security risk! Figure 12 (c/o Google) demonstrates the custom role being applied to a Google Group.

Figure 12: Google Cloud - Custom Role

And here’s a video on IAM and how it can be used! Note we don’t go the organization route, though that may be helpful if you’re structuring a larger organization!

Module video: Cloud IAM Demo [13:13]

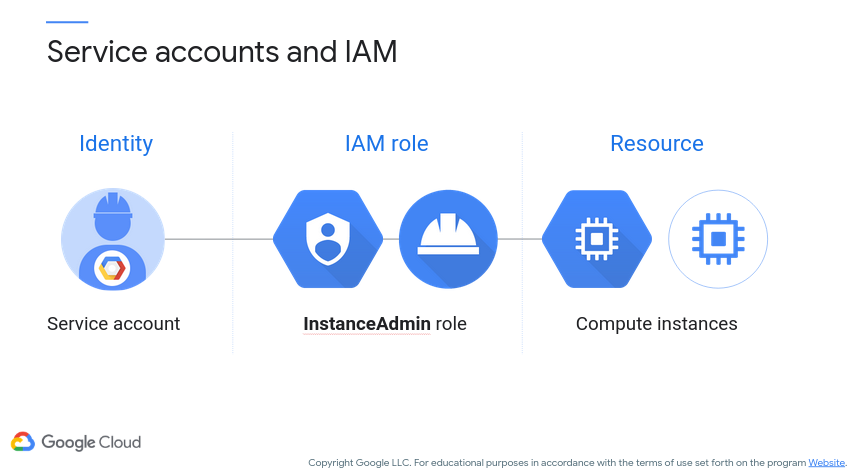

Service Accounts

Thus far we’ve been discussing IAM roles, however service accounts provide another method for cloud security. These accounts enable service-to-service communication/interaction. For example, an application running in a virtual machine needs to access data in Cloud Storage, however you only want that virtual machine to have access to the data. You can create a service account that’s authorized to access that data in Cloud Storage and then attach that service account to the virtual machine. Such service accounts are named with an email address, often ending in *.gserviceaccount.com (e.g., PROJECT_NUMBER-compute@developer.gserviceaccount.com). Think of this as similar to creating a user account for a service in Windows Server or a Linux server.

Keep in mind that service accounts can be assigned IAM roles as well. Figure 13 (c/o Google) shows a service account being granted the InstanceAdmin role over Compute instances.

Figure 13: Google Cloud - Service IAM

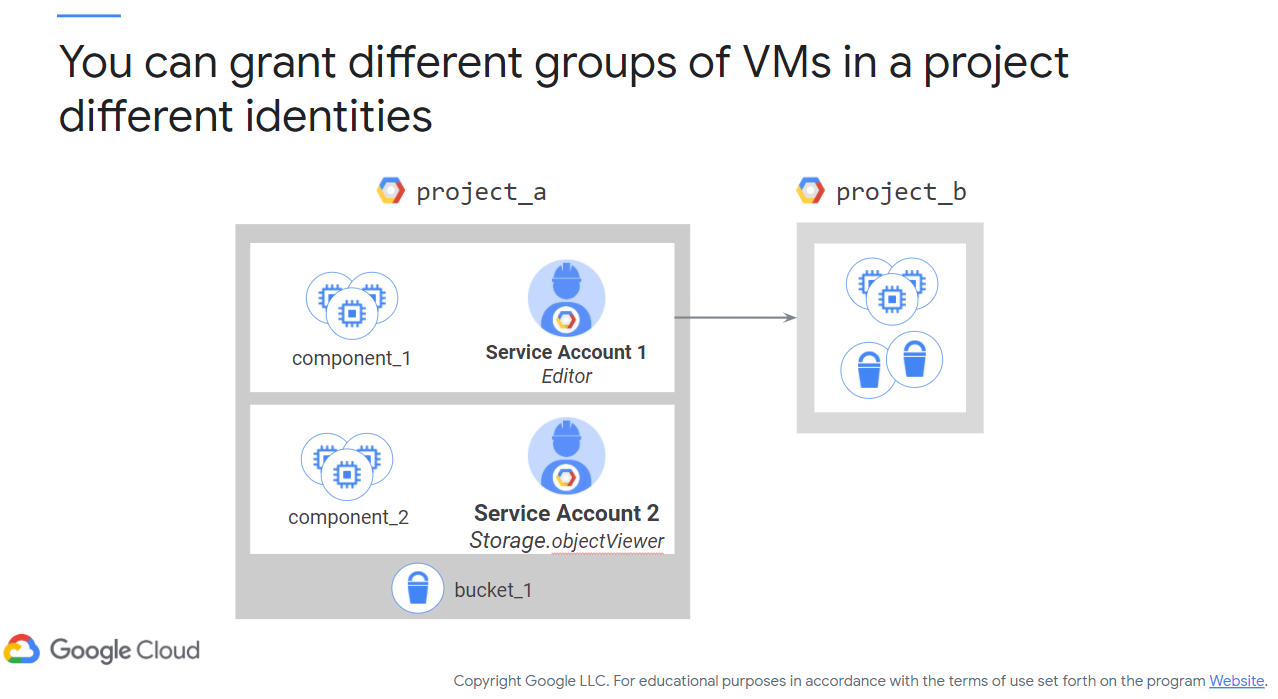

Last but not least with service accounts, you can grant service accounts access to different components within different projects. Figure 14 (c/o Google) shows this activity.

Figure 14: Google Cloud - Multiple Service Accounts

Here’s a more complex scenario. Say you have an application that’s implemented across a group of virtual machines. One component of your application requires the editor role on another project,

project_bbut another component doesn’t need any permissions onproject_b. You would create two different service accounts, one for each subgroup of virtual machines. In this example, VMs runningcomponent 1are granted Editor access toproject Busing Service Account 1. VMs runningcomponent 2are grantedobjectVieweraccess tobucket 1using Service Account 2. Service account permissions can be changed without recreating VMs.

Best Practices

Let’s talk about some best practices now. Note that these are provided by Google, however they can be definitely applied across the gamut of cloud providers.

Resource Hierarchy

- Use Projects to group resources

- Check the policy granted on each resource

- Use “principle of least privilege”

- Use logs

- Audit membership

These steps follow guidelines similar to what is seem in common system administration practices. Ensure that you sandbox your environments as necessary, grouping those that may share a trust boundary (Step 1). Ensure that each resource has the correct policies (i.e., inheritance) applied (Step 2). Ensure that resources only have the privileges necessary to do their job – don’t go above and beyond (Step 3). Lastly, ensure policies are routinely audited to ensure they and their memberships are still valid, using logs and audit memberships (Steps 4 and 5).

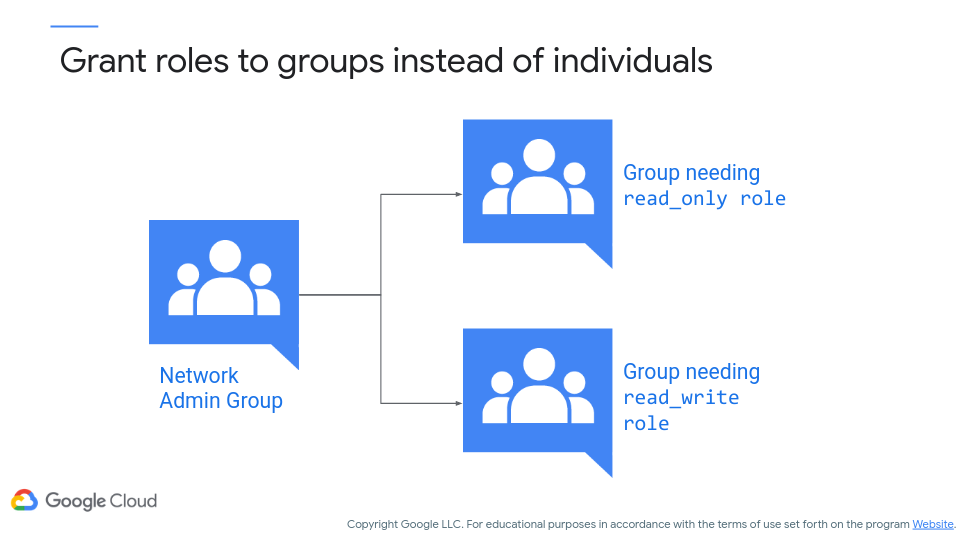

One other point, generally it is better to grant roles to groups rather than individual users, as users may come and go and cause a maintenance nightmare. Better to assign roles to groups and then add/remove users to those groups as necessary! Figure 15 (c/o Google) shows this process:

Figure 15: Group-Based Role

Service Accounts

Now, time for service account best practices (again, c/o Google)!

- Be very careful granting

serviceAccountUserrole

serviceAccountUser has all access to all resources tied to that service account – generally a violation of the ‘principle of least privilege!’

- When you create a service account, give it a display name that clearly identifies its purpose

- Establish a naming convention for service accounts

For Steps 2 and 3, a naming convention and purpose of naming can make your life much easier – you can quickly identify the account and its purpose by intelligently naming them (rather than going through an arduous lookup process!).

- Establish key rotation policies and methods

Another hopefully self-evident task, but ensure your access keys expire regularly and are rotated! Not rotating keys is a great way of opening up your cloud accounts to intrusion.

Lab

You’ll be completing your first Qwiklabs Quest (or Cloud Skills Boost course, yawn - Quest was a cooler name)! This comprises 9 separate labs that takes you through the various facets of security and IAM. For this one, simply run through the course and I’ll check the completion reports.

Additional Resources

- AWS Security Model

- Azure Security Model

- Overview of encryption/decryption

- Google Cloud’s key management service (Cloud KMS)

- Cloud Directory Sync

- AWS IAM approach

- Azure IAM approach

Where noted, the original content was provided by Google LLC and modified for the purpose of the course, without input or endorsement from Google LLC.